By Brand Newland, Pharm. D., and Cal Beyer

Surgeries that are unnecessarily invasive or performed under suboptimal conditions often needlessly increase health plan costs and lead to complications for patients. Creating better pathways to care can help health plan sponsors contain the escalating costs of surgery while contributing to better outcomes for plan members.

The rising costs of surgery have confounded plan sponsors for many years. Surgical procedures are infrequent from an incidence perspective, but they can have a disproportionate impact on health plan budgets and plan member lives.

Approximately 50 million surgeries are performed annually in the United States (Dobson, 2020), and for every 1,000 lives in an employee benefit health plan, it is estimated that between 30 and 50 members will undergo a surgical procedure in a given plan year. The majority of high-cost claimants—members with health care expenses totaling $100,000 or more in a plan year—have had surgery and, in many cases, more than one. Two high-cost claim categories—cancer care and musculoskeletal care—often require surgery.

A 2020 report from the Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker demonstrated that the average cost of inpatient hospital admissions for surgical care nearly doubled from $25,054 in 2008 to $47,345 in 2018. The 2018 Health Care Cost Institute (HCCI) Annual Report revealed that surgery accounted for the largest share of spending among individuals with employer-sponsored insurance, representing 49% of inpatient costs and 37% of outpatient expenses. HCCI further reported that inpatient surgical spending had “the largest cumulative growth between 2014 and 2018, rising 11% over the five-year period.”

More cost increases are likely on the horizon. The COVID-19 pandemic created a backlog of millions of elective surgeries because procedures were delayed for months in 2020. Many reports indicate that the backlog will not be resolved until at least 2023. Even more concerning, cancer screening dropped precipitously during the pandemic. One report estimated that colonoscopies were down by 50% compared with prepandemic levels (Engblum et al., 2022). Missed screenings lead to cancer diagnosis at later, more advanced stages. What once may have been treatable without surgery may now require complex surgical care and lead to higher costs for health plans.

Complications Increase Costs

Surgery-related complications and readmissions further aggravate the economics of surgery, not to mention the member experience. Key complications include:

*Surgical site infections (SSIs): Two to four percent of patients undergoing inpatient surgeries will experience an SSI. These infections are a leading cause of surgery-related readmissions, escalating costs, patient suffering and even death (AHQR). A New England Journal of Medicine study found that nearly one in seven patients hospitalized for a major surgical procedure is readmitted to the hospital within 30 days after discharge.

*Opioid dependence: One of the primary reasons that patients return to the emergency room or hospital following surgery is poorly controlled pain. To that end, an important aspect of preparing for optimal surgery is understanding the options for pain management. The importance of proper pain management and diligent opioid risk reduction cannot be overstated. While rarely reported in this manner, opioid dependence following surgical care is, in fact, a postsurgery complication worthy of attention at the level that SSIs and readmissions receive.

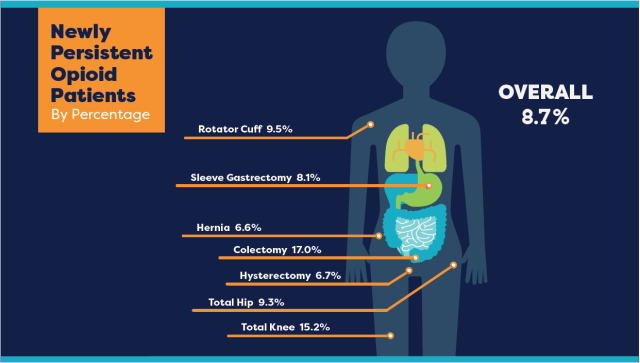

Figure 1 highlights persistent opioid use rates for seven common surgical procedures ranging from 6.6% to 17% with an average of 8.7%. Persistent opioid use is defined as one or more fills of an opioid prescription 91 to 180 days after surgery.

Figure 1: Percent of Newly Persistent Opioid Patients by Surgical Procedure

Driving Optimal Outcomes

While surgery is costly, it is often worth the substantial investment. When a surgery results in the removal of cancer or repair of diseased joints—among many other outcomes—patients’ lives are improved and extended. However, unnecessarily invasive surgery or suboptimal conditions can needlessly increase the costs. Following are common factors that contribute to increased costs.

- Suboptimal site of care: A patient may undergo an inpatient procedure that could have been performed on an outpatient basis.

- Inferior surgery preparation: This can include insufficient proactive pain management education and strategies.

- Inadequate postsurgery follow-up: The patient may be left to navigate recovery on their own.

Surgery cannot be treated as business as usual. The stakes are too high, including rising costs, risks of complications and potentially longer than necessary healing. Delayed recovery times impact quality of life for the patient and productivity and other business results for employers. In short, there is a need to proactively manage surgery.

The following areas may offer solutions to help health plans contain costs and improve the experience for the patient.

Migration From Inpatient to Outpatient Surgery

One strategy is shifting a surgical site from an inpatient to an outpatient setting. This migration is possible in part because of the increased use of minimally invasive surgical methods. However, adoption has not been widespread. The Mayo Clinic has suggested that as many as 93% of knee and hip procedures are suitable for outpatient care, but BlueCross BlueShield (BCBS) reported in 2017 that only 11% of knee procedures and 8% of hip procedures were performed in an outpatient setting.

Shifting knee and hip procedures to an outpatient setting can result in cost savings of between 30% and 40% when compared with the inpatient setting, BCBS reported. Specifically, BCBS reported the following average cost comparisons.

- Knee replacement surgery: The average price for an inpatient procedure is $30,249 compared with $19,002 when performed in an outpatient setting.

- Hip replacement surgery: The average price for an inpatient procedure is $30,685 compared with $22,078 for an outpatient procedure.

Offering a Better Pathway for Surgery

Optimized pre- and postsurgery care support and protocols offer additional opportunities for savings and enhanced member experiences.

Minimally invasive surgery is part of a broader set of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols. The American Association of Nurse Anesthesiologists (AANA), describe ERAS as “patient-centered, evidence-based, multidisciplinary team developed pathways for a surgical specialty and facility culture to reduce the patient’s surgical stress response, optimize their physiologic function, and facilitate recovery.” In other words, ERAS is all about better preparing the patient for the stress of surgery and better supporting the patient each step along the way through their surgery and recovery journey.

ERAS protocols include the following practices.

- Creating tailored nutrition presurgery rather than lengthy fasting

- Using multiple, nonaddictive pain medications to get —and stay—ahead of surgery pain

- Employing techniques to prevent common surgical complications

- Developing strategies to improve the patient’s ability to return to normal life function sooner

The ERAS Society website provides sample standardized guidelines (protocols) for at least 21 distinct types of surgery.1

Benefits of ERAS

Surgical leaders have highlighted several key outcomes from implementing ERAS guidelines, including substantial reductions in postoperative complications, length of stay and overall costs. At the same time, both patient and staff satisfaction increased.

Patients who receive ERAS-based care on average have:

- 30% shorter hospital stays

- 50% fewer complications

- 90% reduced opioid use

- Thousands of dollars in savings per surgery

- Faster return to normal life and work.

Hah et al (2021) confirm the economic burden surgery has on patients and employers from lost wages and lost productivity.

Many researchers have identified the risk of anxiety, stress and depression occurring in patients before and after surgery. There is rising interest in embedding mental and behavioral health screening into presurgical patient risk assessments. Robertson (2022) describes a surgical practice doing so focused on a preoperative behavioral health assessment and a personalized perioperative pain management plan.

This is significant since one of the hallmarks in the ERAS protocols is opioid-sparing techniques, which include the use of nonopioid medications as well as multimodal pain relief. Research demonstrates ERAS protocols reduce the amount of prescribed opioids by up to 90%.

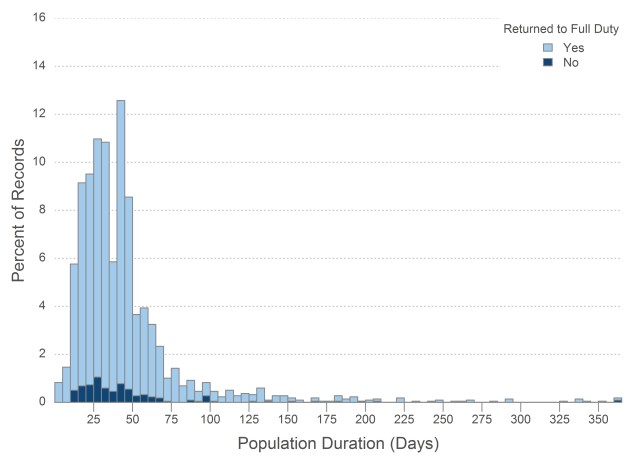

Traditional surgical approaches—those employing outdated techniques, large incisions and opioid-first pain management approaches—lead to widely variable results. In fact, the status quo in surgery leads to widely variable outcomes not only in terms of recovery time but also in terms of costs, risk of readmission, risk of opioid dependence, patient satisfaction and other meaningful measures of quality. Figures 2 and 3 show the wide variation in recovery times for hernia repair and knee replacement surgeries.

Enhanced recovery-based surgery can minimize outliers and achieve high-quality experiences or patients.

Figure 2: Distribution of Return-to-Work Times—Hernia Surgery

*Copyright with permission of ReedGroup, 2022.

Figure 3: Distribution of Return-to-Work Times—Knee Replacement Surgery

*Copyright with permission of ReedGroup, 2022.

Recommended Strategies for Self-Funded Employee Benefit Plan Sponsors and Trustees

Surgery is an important aspect of employee benefit plan management and oversight. The business case for better understanding the costs and outcomes associated with surgery is increasingly clear. Surgery is a major direct expense for employee benefit plan claims, a leading gateway to new persistent opioid use cases and a significant indirect expense in lost productivity due to longer than necessary recovery and delayed return to work.

Employee benefit plan sponsors and trustees may want to consider adopting the following strategies to help generate better outcomes and reduce costs.

1. Analyze Data

By conducting an analysis of historical medical and pharmacy data for all surgery-related claims over the past two to three plan years, sponsors may discover opportunities for improvement by identifying the percentage of surgery performed as inpatient procedures compared with outpatient, the percentage of minimally invasive procedures, and the percentage that use opioid-sparing and multimodal pain management strategies. For example, plans can emphasize analyzing data for surgery cases that exceed a certain dollar threshold, all high-cost claims or specific procedure such as hip and knee replacements. The use of ERAS strategies helps increase the percentage of outpatient surgeries because, for example, it ensures that the patient has adequate pain control (not to mention realistic expectations) and can be home without around-the-clock monitoring by a health care facility.

2. Consider Nurse Navigators

Surgical nurse navigators provide education and advocacy to patients and caregivers on preparing for and recovering during the surgical experience. Plans can start by asking their third-party administrator about what resources and care management programs it has and how it can assist in improving surgical quality, creating faster recovery times and reducing surgical complications

3. Clearly Communicate Precertification Processes

Clearly explain the rationale for any required surgical or diagnostic imaging precertification processes to plan members in annual open enrollment documents. This should include step-by-step procedures and should also be spelled out in the plan’s benefits guide. Including information about precertification processes for diagnostic imaging is recommended since imaging services frequently precede surgery. Using precertification processes for both inpatient and outpatient procedures also enables surgical nurse navigators to improve patient education, better establish expectations and help members to modify behaviors, all of which contribute to better outcomes.

4. Educate

Create educational materials for plan members who have conditions that may require surgery. The educational materials can be simple documents designed to be shared with members to explain surgical quality initiatives, such as questions to ask your surgeon before surgery, preparing for surgery, and pain management options before, during and after surgery. The sidebar “Preparing for Surgery” provides a list of questions plan members should ask health care providers prior to surgery. Additional examples of vital educational messages include proper disposal of leftover opioids following surgery, opioid-sparing pain management for caesarean deliveries and for persons in long-term recovery.

5. Address Pain Management

Evaluate and adopt both pharmacological and nonpharmacological options for perioperative surgical pain relief in your plan. Members having surgery should be educated to ask their doctors if there are options other than opioids. An example of a pharmacological option is multimodal pain relief using prescription medications as well as nonopioid prescription medications. Examples of nonpharmacological options include acupuncture, neurostimulation, as well as mindfulness exercises, physical therapy, and massage therapy.

Conclusion

Surgery is costly. The economics are driven by the ever-increasing costs of overall health care as well as unique factors, like those related to delayed care and missed screenings during the pandemic.

Surgery need not be so expensive, however. Surgery becomes expensive when the first procedure fails, when the patient experiences a complication and readmission, when the employee misses two extra months of work they cannot afford to miss and when a colleague inadvertently becomes dependent on opioids.

In the workplace, upon learning that a co-worker requires a leave of absence for surgery, the standard response has been to offer best wishes, to tell them to take all the time they need and then, in effect, to lean away. The results of this approach are increased health care costs, increased risk of developing an opioid use disorder, wasted medication and lost productivity due to longer recovery times.

References

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). “Surgical Site Infections.” https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primer/surgical-site-infections.

American Association of Nurse Anesthesiology (AANA). “Enhanced Recovery after Surgery.” www.aana.com/practice/clinical-practice-resources/enhanced-recovery-after-surgery.

The American College of Surgeons. “Strong for Surgery.” www.facs.org/for-patients/strong-for-surgery.

Beyer, Calvin and Brand Newland. (October 10, 2021). “Optimizing Surgical Outcomes.” https://www.insurancethoughtleadership.com/optimizing-surgical-outcomes.

Beyer, Cal, Richard Jones and Brand Newland. 2022. Construction Financial Management Association. Building Profits. “Waging a Counterattack on Opioids in the Workplace and at Home.” https://cfma.org/articles/waging-a-counterattack-on-opioids-first-dose-prevention-strategies-for-the-workplace-and-at-home.

Blue Cross Blue Shield. January 23, 2019. The Health of America Report: Planned Knee and Hip Replacement Surgeries are on the Rise in the U.S. www.bcbs.com/sites/default/files/file-attachments/health-of-america-report/HoA-Orthopedic%2BCosts%20Report.pdf.

McDermott, Daniel, Julie Hudman, Dustin Cotliar, Gary Claxton, Cynthia Cox and Matthew Rae. (November 4, 2020). The cost of inpatient hospital admissions for surgical and medical care nearly doubled from 2008 to 2018. Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker. www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/how-costly-are-common-health-services-in-the-united-states.

Dobson, G. P. “Trauma of major surgery: A global problem that is not going away.” International Journal of Surgery. September 2020; 81:47-54. Epub 2020 Jul 29. PMID: 32738546; PMCID: PMC7388795. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.07.017.

Englum, B.R., N. K. Prasad, R. E. Lake, M. Mayorga-Carlin, D. J. Turner, T. Siddiqui, J. D. Sorkin and B.K Lal. (2022), “Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on diagnosis of new cancers: A national multicenter study of the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System.” Cancer, 128: 1048-1056. doi.org/10.1002/cncr.34011.

ERAS® Society. “Guidelines.” https://erassociety.org/guidelines.

Feder, O. I., K. Lygrisse., L. H. Hutzler, R. Schwarzkopf, J. Bosco, R.I. Davidovitch. “Outcomes of same-day discharge after total hip arthroplasty in the Medicare population.” The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2020; 35:638–642. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2019.09.040.

Hah, J.M., E. Lee, R. Shrestha, L. Pirrotta et al. “Return to work and productivity loss after surgery: A health economic evaluation.” International Journal of Surgery. Vol. 95, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.106100.

Health Care Cost Institute (HCCI). 2018 Health Care Cost and Utilization Report. https://healthcostinstitute.org/images/pdfs/HCCI_2018_Health_Care_Cost_and_Utilization_Report.pdf.

Muñoz E, W. Muñoz 3rd and L. Wise “National and surgical health care expenditures, 2005-2025.” Annals of Surgery. 2010 Feb; 251(2):195-200. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181cbcc9a. PMID: 20054269.

Popke, Michael. May 11, 2022. “Benefits Pro. Cost pressures could drive more employers to seek Centers of Excellence.” www.benefitspro.com/2022/05/11/cost-pressures-could-drive-more-employers-to-seek-centers-of-excellence.

Reed Group. (2021). MDGuidelines. www.mdguidelines.com.

Robertson, M. July 22, 2022. Becker’s ASC Review. “A New Standard of Care: Why this Texas practice evaluates mental health ahead of surgery.” www.beckersasc.com/asc-news/a-new-standard-of-care-why-this-texas-pre-op-screening-center-evaluates-mental-health-ahead-of-surgery.html.

Tsai, T. C., K. E. Joynt, E. John Orav et al. “Variation in Surgical-Readmission Rates and Quality of Hospital Care.” The New England Journal of Medicine. 2013; 369:1134-1142. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMsa1303118.

Brand Newland, Pharm.D., is the chief executive officer and co-founder of Goldfinch Health based in Austin, Texas, where he works to institute a higher standard of care in surgery and optimized recovery through enhanced surgical care protocols. Newland holds a Pharm D. degree from the University of Iowa and an M.B.A. degree from the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. He can be contacted at brand.newland@goldfinchhealth.com.

Cal Beyer, CWP, is vice president of workforce risk and worker wellbeing for Holmes Murphy & Associates. He is a member of the executive committee of the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention and an advisory board member for the Suicide Prevention Resource Center, Youturn Health and MindWise Innovations. He can be contacted at cbeyer@holmesmurphy.com.

Endnote

- A list of ERAS Guidelines for various surgical procedures is available at https://erassociety.org/guidelines/

The latest from Word on Benefits: